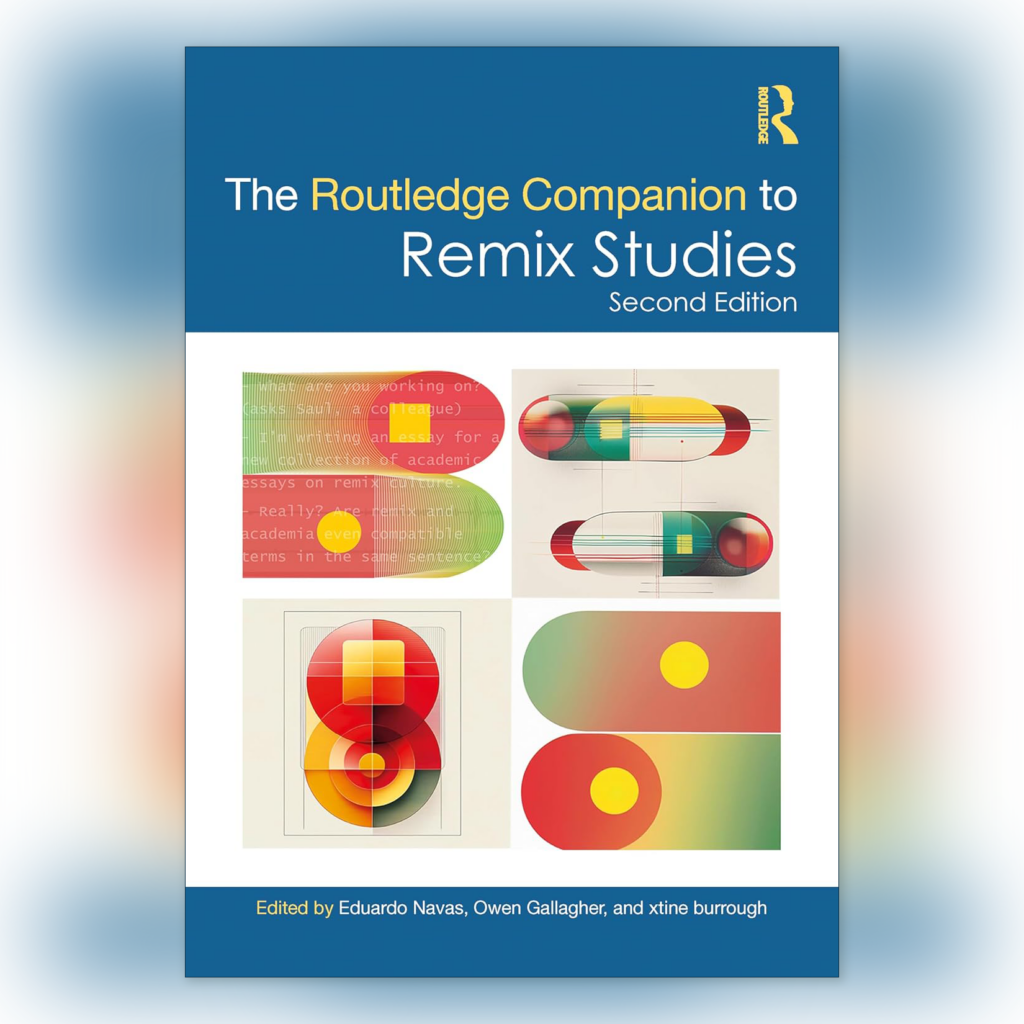

Our new book is out! We started working on this huge project back in 2022 and after a lot of hard work co-editing and writing with my friends and colleagues Eduardo Navas and xtine burrough, and our 50+ contributors, the 2nd edition of The Routledge Companion to Remix Studies, updated and revised for the age of AI, is officially published!

More details here: https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Companion-to-Remix-Studies/Navas-Gallagher-burrough/p/book/9781032509105

We’d really appreciate it if any interested friends and colleagues could consider requesting their university libraries to order a copy. The hardcover is intended primarily for libraries (thus the price tag), but there’s also an ebook available now.

A huge thank you to all of our incredible contributors, listed below, organised by section:

Part 1: History – Martin Irvine, Scott Haden Church, Vito Campanelli, Kembrew McLeod, Cicero Inacio da Silva, Margie Borschke, Eli Horwatt, Grazia Ingravalle, Kathleen Williams

Part 2: Aesthetics – Lev Manovich, Nicola Maria Dusi, Erandy Vergara, Tashima Thomas, Dale Hudson, Roy Christopher, David Gunkel, Monica Tavares, Marcus Boon

Part 3: Ethics – Aram Sinnreich, Mette Birk, Janneke Adema, Patricia Aufderheide, Brandon Butler, Katharina Freund, Lucia Tralli, Mark Amerika, Erin Reilly and Sam Hewitt, Ragnhild Brøvig

Part 4: Politics – Rachel O’Dwyer, Paolo Peverini, Olivia Conti, Conor McGarrigle, J. Meryl Krieger, Rachel Falconer, Hannes Liechti, Nadine Wanono

Part 5: Practice – Tom Tenney, Gustavo Romano, Jonah Brucker-Cohen, Heidi Biggs, Luke Meeken, Kory J. Blose, Robbie Fraleigh, Alexander Korte, Eduardo de Moura, Nate Harrison, Emily Erickson, Elisa Kreisinger, Eric Faden, Diran Lyons, Jesse Drew, Kevin Atherton

Navas, Eduardo, Owen Gallagher, and xtine burrough, eds. 2025. The Routledge Companion to Remix Studies, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.